ANNINA NOSEI

Interview by Michael Bullock

Photgraphy by George Etheredge

Blau Magazine Issue no.11, 2024

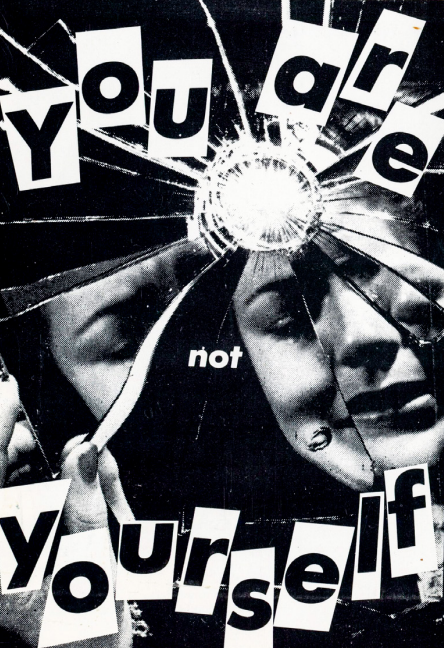

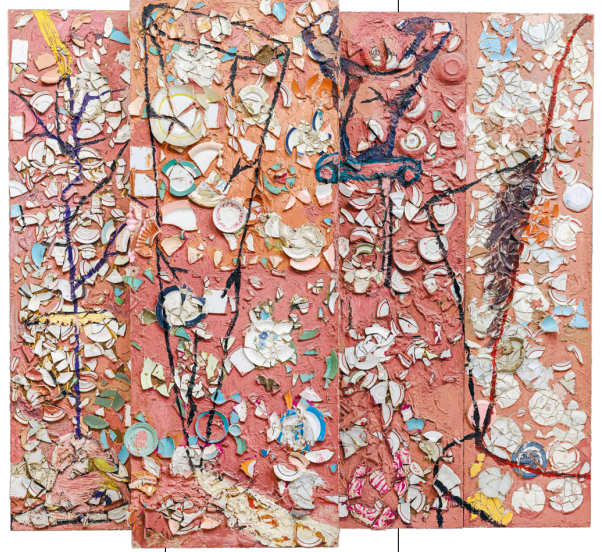

Art oracle, former gallerist, and award winning ballroom dancer Annina Nosei ushered in a generation of world renowned artists. Having grownup in Rome, she viewed the emerging 1980s New York City scene through the long lens of European art history, identifying some of the most significant works of her time. She started informally showing artworks in a SoHo loft she shared with Larry Gagosian in the late 1970s, and by the early ’80s,she had her own space and a reputation for discovery. Keith Haring, Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, Richard Prince, and David Salle all count among those she supported in the early stages of their careers. Nosei was particularly instrumental in launching the career of Julian Schnabel. Shepurchased his very first plate painting, The Patients and the Doctors (1978), and hung the ungainly, ambitious work in her foyer, where it would be discovered by Schnabel’s longtime gallerist, Bruno Bischof berger. Before my interview with Nosei, Schnabeltook a moment to call me to sing her praises. With his signature bravado, he told me, “Nosei is a visionary, with the generosity and temperament of an artist.” While her record of discovery is broad and undeniable, her legacy will forever be linked to her unique relationship with one artist—Jean-Michel Basquiat, whom she met when he was 20. She nurtured the young artist, encouraging him to transition from spray paint on buildings to acrylic paint on canvases. Shortly after that, she provided him with his first studio space in the basement of her gallery, and then presented his first few solo exhibitions—a prolific relationship that Schnabel would memorialize in his first feature film, Basquiat (1996). Now in her mid-80s, the outspoken legend would have you believe she’s the last person interested in her own legacy. She’s not nostalgic in recounting her career, framing her decisions as those of a pragmatic business person. Yet, in rare moments, she breaks character, and I was able to get a glimpse of how she was impacted bythe art she helped make famous.

Michael Bullock: How are you today?

Annina Nosei: Medium, because I’m old.

Well, you’ve lived an exceptional life. You have played a significant part in the story of 20th-century art. Let’s start with your upbringing.

My father was from Florence. He was a classics professor, so I come from a family of Latin and Greek and ancient history. And although I’m part of the 20th century, the art I found in that century was not what I was accustomed to in Rome, because of the churches, the frescoes of the ancient Romans, and then pieces from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance... Many beautiful Caravaggios are close by. If you think about the 1800s, once you come to 1900, the art is a little bit less interesting than it used to be. Then, even closer, there’s the 1960s, with commercial art and then abstract art, which is a big mess.

What about your mom?

My father, my uncle—everybody was a professor, but my mom was from Poland, and she was partially the ambassador of Italy to Poland and so on. She spoke five languages.

Coming from a family of intellectuals, with your mother in politics, was art a logical trajectory for you?

No.

Did you always want to work with artists?

Before going to Paris, I worked at a gallery in Rome that is now connected to the Marlborough Gallery. And I knew a lot of artists and a lot of people involved in film. Then, when I went to Paris and worked for Ileana Sonnabend, I met alot more people, particularly Rauschenberg, because in 1964 he won the Golden Lion. So I had to go from Paris to Venice to make sure the paintings from the American Academy made it to the Biennale. In Venice, Rauschenberg asked me if I’d work for him. He was involved with John Cage, and they were doing a show at an Italian theater for the Biennale. I was asked to be a translator, so he gave me a piece of paper with instructions for lighting. He was a great artist, but he was dyslexic, so the lights were coming up in the opposite places. It was a mess. John Cage loved it, because he loved chaos. I’d also worked with Carolee Schneemann in Paris. One thing that I had to do was be hung on the wall with tape. An artist who obviously copied this is Maurizio Cattelan. He made something everybody talked about, a banana stuck on the wall. Have you seen it?

Oh, yes, and you’d already done this much more dramatically in the 1960s?

I’m sure he took it from me. I don’t particularly like it.

And Rauschenberg also introduced you to your husband?

Yes, John Weber. He’d been the director of Martha Jackson Gallery, which at the time was a big gallery in New York. He wanted to show Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol, but Martha didn’t like the paintings he was interested in. So he left, and he went with Dwan Gallery in Los Angeles. That’s whereI met him. Only, since I was in America on a Fulbright, I had to leave. So I wrotea letter to a congressman in Hollywood. Whatever I said, it got me my permanent visa within a week.

Nicely done! So, you moved to New York as a couple?

We were married, yeah. I taught art history at Kingsborough Community College and was also the director of their gallery. I was supposed to be granted tenure, but they didn’t offer that to women in that period, so I sued them and won. But in the meantime, there was a moment where I had nothing to do, and I started to sell art and eventually began working with a young man named Larry Gagosian.

I wanted to buy more Twombly drawings and was told that there was another person who also wanted them. So, I called him up and said, “Larry, we want the same thing from the same artist. We are raising his prices!” So we started to do things together. I was under 40, and he was maybe six years younger. He was based in Los Angeles, but he and I rented a loft together on West Broadway in New York City. He would send paintings. I would send paintings. We sold a lot of stuff.

So together you two covered a lot of ground.

I’d call him up and say, “Can you find me a Jasper Johns?” The next one I’d find for him, and he’d sell it. He bought me a Twombly sculpture that he’d found in Los Angeles, and I sold it the next day to an artist in New York.

You were a good team?

In a sense. We collaborated, yes, but we weren’t officially business part-ners. If I found something and it didn’t involve him, I could do it myself. We shared the studio because he lived in Los Angeles and I live here, and it was a place to store the paintings and sculptures. Eventually, I decided touse it to make a couple of shows. I asked David Salle, and I sold some ofhis paintings to Mary Boone and some to Peter Brant. Larry also bought some, and I kept one. I sold them to everybody. I sold them all. I always sold everything. I’m not a collector.

Why did you pick Salle?

It was interesting because across the street, John Weber was showing Robert Mangold paintings. They were the same color except they had lines, straight lines. And then instead, David’s added something a little human...

It was funny to me, because I come from Rome where the American art was “good art.” Was it good art?

I think so. I don’t know.

You still don’t know?

I don’t know. I saw them all...

Would you say you discovered David Salle?

Right.

I called him to ask about you.

What did he say?

He said something along the lines that you were friendly with most of the important artists in the generation above yours, and that usually people in power stick to the establishment, but you were one of the few people in New York who extended your focus to the generation below your own, and because of this you were key in helping establish some of the most recognized artists of the ’80s.

I’ll tell you more about that in a minute. But I have to say, even before I had the loft, I had a lot of paintings here. Mary Boone would come. She’s great. She immediately understood what I understood. Super smart and always very nice with me.

I imagined you two were competitive.

No, no, nobody else has been as nice to me as Mary Boone. I bought from her. She actually sold me Julian Schnabel’s most important painting. People have been known to say strange things about her, but I have always liked her.

It’s rumored that she stole your biggest discoveries. Salle, Basquiat...

I called Larry and said, “I’m going to open a gallery.” I found a place and I built a gallery with all kinds of artists I knew. But one important day, David Salle told me, “Sorry, Mary Boone has asked me to be part of her gallery.” “Congratulations,” I said, “that’s great!” I was very happy. She also bought a painting, and she sent me a whole show for free.

What do you mean a whole show?

Yes, of Salle’s drawings.

Why?

Because she’s a nice person. The fact is that Mary Boone has been nice to me all her life. When she had to go to prison because of tax evasion, I thought it was really sad. I was afraid that they were going to come after me because I had not yet paid a certain type of tax. I was worried they might try to take away my visa. So, you know what I did? With the help of an immigration lawyer, I brought them two letters. One was from Hillary Clinton, because I met her at a party and we had kept in touch, and the other was from George W. Bush. I had his address, I wrote him a letter, and he wrote me back and said all kinds of nice things about me.

How did you meet him originally?

I never met him. I just wrote him a letter.

When was this?

In 2008. George still sends me a Christmas card, I don’t know why. He’s a painter, a good painter. Maybe that’s why.

Wow. But didn’t you have citizenship from marrying John Weber?

No, at that point we were divorced, but we always stayed friendly with each other.

So, you showed David Salle and that went well. What were some of the next shows?

Another person who was shown at the West Broadway space

was Richard Prince.

Before he was known?

Yeah. I liked his work.

What did you like about it?

I don’t remember.

OK. Let’s move on to Julian Schnabel. You bought his first plate painting?

I didn’t show him because he was showing with Mary Boone, but I had The Patients and the Doctors hanging right there on that wall. I liked it a lot. Much better than now, because Schnabel took it back from me and hung it in the light, so the colors are less beautiful than when I owned it...The first time that the ’80s artists’ work started going to auction, I called him up and said, “I want to put it up for auction,” because I paid nothing for it, $2,500 or less. He said: “No, don’t put it up. I’ll take that one back from you and give you another one to sell at auction. I like that one too much.” I agreed but re-quested a minimum return of at least $65,000, whether the replacement soldor not. We signed that agreement, and he gave another painting to Sotheby’s (Notre Dame, 1979). That replacement was much less beautiful than the onethat I originally owned, but it went formore than $100,000.

Perfect. So, everyone’s happy.

That’s it.

Julian told me that both The Patients and the Doctors and Notre Dame are on display together for the first time at his son Vito’s gallery.

Yes, I saw them, but they’ve lost their color.

He called me today to say—again, I’m paraphrasing—that you’re a visionary and that you bought his ungainly painting that was hard to understand. But you put it in your home, in your foyer, when he was just starting his career. He said he wished all collectors would take these types of risks. Because of you, Bruno Bischofberger saw his painting and decided to start working with him. He said that you have the generosity and temperament of an artist.

I don’t know...

You picked up all these artists who had never shown before, but who then went on to become internationally respected. I know it may be hard to describe, but can you try to explain your incredible instinct for new talent?

Well, when I started the gallery, I decided to do some Italian artists.

Established artists?

Medium. Mimmo Paladino was one. I love Pizzi Cannella’s paintings. He drank too much. I also showed artists who were very well known. Karel Appel, for instance. He liked to come to the gallery because he liked Basquiat. You probably want to talk about Basquiat.

Are you bored of talking about Basquiat?

Before he was in the gallery, I showed many Europeans. But at a certain point I decided to find some American artists. I went to PS1 and saw a show curated by Diego Cortez, New York/New Wave. There were at least a hundred artists, and I saw two that I liked: Basquiat and Roberto Juarez. I couldn’t show Roberto because he was already with the Robert Miller Gallery—luckily he’s still alive and making the most beautiful paintings. When I came home from the show, I called somebody named Basquiat in Brooklyn. He wasn’t there. He called me back. I wasn’t there. Then I went to an opening, and this young Black kid came over to me, wearing mascara. He asked me to come see his drawings in his girlfriend Suzanne Mallouk’s room. He was 20 years old, maybe even ten years or more after I closed it, Prada, which of course owns Miu Miu, sent an agent to tell me that they wanted to rent that place. I said yes and I went to Chelsea. My ex-husband said: “What are you doing? You’re leaving SoHo, leaving everybody!” Yes—and everybody eventually followed. So, yes, I still own it. And I get a lot of money from Prada.

What was Basquiat like then?

He was intelligent, he wanted to talk about a lot of things. He loved music. It actually drove me crazy, because he had music on all the time that I could hear upstairs in my office—“Stop, I can’t take it anymore!” But he kept making paintings, and

people immediately came to buy them.

Did you keep any of his paintings?

I kept one. Later, I told him to leave the gallery because of drugs. I came back from Italy and saw him with a guy—it was obvious he was using. I said: “What are you doing? You’re inviting people who sell drugs to my gallery?” He said, “Don’t tell my father.” I said, “No, on the contrary, I’ll tell your father.” And then I asked, “Why don’t you talk with my ex-husband, John Weber?” He was an older man, so I thought maybe Jean-Michel would listen to him. So, John came and they talked for a bit, but afterward John said to me: “Annina, I know you. I know your family, I know your father, I know your aunts—I know everybody. We have a daughter together. I understand you like art. But why do you have to do it with somebody who is involved with drugs?” I said, “You’re right.” So, when Jean-Michel came back, I told him: “You have to leave the basement. Don’t worry, I will rent a loft for you on Crosby Street for one year, and you can do whatever you want there.” I did Documenta with him and I organized the show at the Galerie Delta in Rotterdam—those were the only two things I wanted to do with him.

You left him on his own at the height of the hype?

He got involved with a very important man: Stephen Torton. Everybody talks badly of him because people are stupid. Anyway, Stephen became Jean-Michel’s assistant,and he did something major. Rather than using the regular canvases you’d put on a wall, they were canvases hanging with pieces of wood sticking out, like across. They were all like that. These were not middle-class paintings. They were something else. I liked it because they weren’t sculptures and they weren’t just paintings. Yes, they were on the wall, but they were different.

So, he was more than an assistant. They collaborated?

Stephen worked for him for two years. Even though it was something Jean-Michel experimented with in one early painting something sticking out from the canvas it wasn’t in the

brillian tway that Stephen did it for him.

How do you feel about your depiction in Julian Schnabel’s 1996 film Basquiat?

Ah, the movie.

What do you think about it?

Jeffrey Wright, who played Basquiat, he is a great actor. I’ve also seen him in the theater. He’s fabulous. I don’t remember anything else.

You don’t remember who played you?

Am I in that movie? I don’t think so.

You are. Your character brings collectors into the basement studio to introduce them to Basquiat, and your character says something like, “This is the true voice of the gutter!”

I don’t remember.

So, it didn’t affect you.

No, but I like that actor.

There is something I don’t understand though, you didn’t want drugs around your family, but in the 1980s New York art world, weren’t drugs a normal part of social life?

I don’t know, because I didn’t see it. I wasn’t in the gallery all the time. I went to dance studios—I was involved in sports all my life, I wasn’t interested in that kind of thing, whatever it was.

What sports?

When I was little, hurdling. Then I played tennis, then I rode horses. I have a house in upstate New York, and when I was around 40, Irving Blumcame to visit because Ellsworth Kellyhad a studio close by. He saw me coming back exhausted and said to me,“Stop with the horseback riding at your age, because you’re going to fall again.” I had already fallen twice. Blum told me, “You’re going to end up like Christopher Reeve. Find something else.” And that’s what I did. I went to the Fred Astaire Dance Studios because theysent me a piece of paper for one month of free lessons. The instructor there encouraged me to go to a competition. I said, “Me? Already?” He said, “Yes,you can do it.” So, of course I went and I won.

A ballroom-dancing competition?

Right. When we went to the competition, he brought his wife and also a Russian guy with his wife, and a fellow student who was a designer. I not only won the competition but I ended up selling a lot of paintings to the designer. I decided I no longer needed dancing lessons but kept on participating independently. Over the years, I won a lot of competitions.

Do you still dance?

Not now, no.

Does Basquiat’s enormous place in art history and pop culture surprise you?

He always made a lot of paintings. I hoped there would’ve been more. Once, he was doing a drawing on the floor, talking to me about Greek mythology, and he went on and on and on. It was fabulous what he was doing, drawing on the floor, writing a lot of things, one after another. It became so frantic that he did the last corner in all black. I gave it the title Pegasus (1987), and it was the most beautiful drawing. I could have bought it, but I didn’t want to give him any more money for drugs, because he was killing himself.

When you think about your own legacy, what are you most proud of having accomplished? What sticks out in your

mind?

Why? My own daughter doesn’t care.

Why not?

Because she has her own problems.

Well, you had a powerful impact on the careers of many of the most important artists of the ’80s, a period when there were still only a handful of female gallerists. What is a show that you’re especially proud or fond of?

There is something I did that I liked, a 1985 group show called The Door that I also wrote the catalogue for, and I liked it because all the works were doors. There was Karel Appel,

Basquiat, Pizzi Cannella, LeWitt, Rauschenberg, Schnabel, Vincent Gallo...

Vincent Gallo who became an actor?

Right, he became an actor. He did a fabulous show where I sold everything. Over the years, he has tried to buy some of this work back, but no one ever wants to sell them.

Why doors?

I wrote in the catalogue that there cannot be a better metaphor for art than the door, because the door is the ideal symbol for the function of art. What a metaphor does is invite the extension of meaning. For me, the door assumes that symbolic function.

That’s a beautiful place to end, would you like to add any closing thoughts?

No.

You’ve already said a lot of great things.

I’ve said a lot of things.